After economic ‘rupture’ with U.S., Canada looks to Asia for oil exports

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney has signed a sweeping agreement with the government of Alberta, home to the country’s vast tar sands oil reserves, laying the groundwork for a new oil pipeline to transport oil to British Columbia’s northern coast for export.

With Canada engaged in an increasingly tense trade war with the United States, Carney is seeking to send more of Canada’s oil to Asia and to develop stronger energy sector relations with Pacific Rim countries. Canada is far from the only country pursuing trade agreements that eschew the U.S., which has become a hostile trading partner under President Donald Trump.

Carney, a former special U.N. envoy on climate change and leader of the Liberal Party, which pursues a greenhouse gas-reducing agenda, is a surprising figure to lead the charge for a major oil pipeline that will transport hundreds of millions of barrels a day of bitumen – a super-heavy, dense form of crude oil found in oil sands – across Western Canada.

To moderate the pipeline’s impact and his government’s image, Carney is also promising to build the largest carbon capture and storage project in the world in Alberta, all while reaffirming that Canada and Alberta remain committed to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, the agreement between Carney and Danielle Smith, Alberta’s premier, also lifts a cap on emissions from Alberta’s oil and gas sector, exempts the province from regulations phasing out fossil fuel electricity generation, and extends a deadline to reduce methane leaks.

While the agreement doesn’t mention the U.S. explicitly, Carney said that the fact that 95 percent of Canada’s energy exports go to the U.S., while once a strength, “is now a weakness.”

“The global economy is rapidly changing,” Carney said. “As the United States transforms all of its trading relationships, many of our strengths – based on those close ties to America – have become our vulnerabilities.”

Carney, a former banker, called this new geopolitical reality “a rupture, not a transition,” and said it means that Canada’s “economic strategy needs to change dramatically and rapidly.”

The Canadian government estimates that U.S. tariffs and the uncertainty they are causing will wipe $50 billion from Canada’s economy. After taking office, Trump imposed a 10 percent tariff on crude oil imported from Canada to the U.S.

The Trump Administration’s ouster of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and attempted takeover of the Venezuelan oil industry reinvigorated those in favor of the pipeline, as increased flow of heavy crude from Venezuela into U.S. refineries could reduce the market share forCanadian producers, which export the same kind of heavy crude.

Stewart Prest, a political scientist at the University of British Columbia, said the simplest argument for the pipeline is that it will enable the country to move away from dependence on the U.S. as its biggest customer at a time when relations are unstable and unpredictable. Carney has suggested the pipeline “will act as a driver of change for the country's economy — a kind of catalyst enabling investment in everything from renewable energy to carbon capture technologies,” Prest said.

Prest thinks some of the claims have validity, though none are completely convincing.

“Access to Asian markets are great in theory, but of course as other societies move towards a low carbon future, those markets will not last forever,” Prest said. “More ominously, the U.S.'s military action in Venezuela in theory paves the way to long-term lower prices for heavy oil — precisely the kind Canada sells. This increases the urgency of diversification but also means Canadian oil may become less competitive. At some point, Canadian oil will be uncompetitive, and that day may come sooner than many Canadians think.”

Prest said that if the new pipeline runs through the area of British Columbia currently proposed, it would expose protected and vulnerable temperate coastal rainforest to the threat of oil spills. The area is currently under a moratorium on oil tanker traffic because of concerns about spills.

Canada’s Indigenous communities also largely oppose the project because of the government’s failure to consult with them as required by law, Prest said.

“Indeed, in my opinion the government's approach is at risk of failing to meet constitutional requirements in this regard,” Prest said.

Canada’s assembly of First Nations unanimously voted for a motion calling for the agreement to be scrapped. This includes rejecting any changes to the current oil tanker ban off the Northern coast of British Columbia.

Within hours of the agreement’s signing in November, Steven Guilbeault, a former environment minister, announced he was leaving Carney’s cabinet. In a social media post, he criticized Carney’s government for failing to consult “with the Indigenous nations of the west coast of British Columbia or with the provincial government, who would be greatly affected by this agreement.”

“Furthermore, a pipeline to the west coast would have major environmental impacts, particularly as it could cross the Great Bear rainforest, contribute to a significant increase in climate pollution, and move Canada further away from its greenhouse gas reduction targets,” he wrote.

Guilbeault also warned that allowing oil tanker traffic off the coast of British Columbia would significantly increase the risk of accidents in the region.

In anticipation of this type of fossil fuel expansion, the Carney government passed the Building Canada Act in June, giving his administration the power to override environmental regulations and fast-track projects in the national interest.

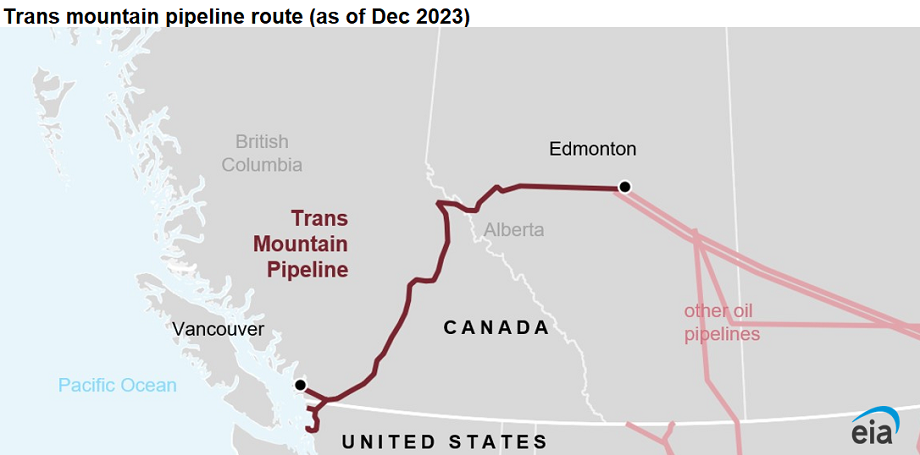

Over the last decade, energy companies have proposed several major Canadian oil pipelines, including the Keystone XL, which would have brought Canadian oil sands to the U.S. All but one, the Trans Mountain expansion (TMX), have failed due to regulatory hurdles and environmental opposition. The Trans Mountain pipeline carries crude oil from Edmonton, Alberta, to the southern coast of British Columbia. Opening in May 2024 after more than a decade of controversial progress, the expansion increased capacity from 300,000 to 890,000 barrels per day. The TMX was originally forecast to cost $5.4 billion Canadian dollars and ended up costing $34.2 billion, according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Tom Gunton, a professor in the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, does not believe Canada needs another costly pipeline transporting oil for export from British Columbia. He pointed out that the government is losing money on the Trans Mountain expansion because the tolls paid by oil companies are based on outdated contracts that fail to cover the full costs of building the pipeline.

“Building a new oil pipeline would be a costly mistake for both Alberta and Canada,” Gunton wrote in an article for the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “World oil demand is likely to peak in the next few years, and existing pipelines have the potential to provide adequate capacity at lower cost and risk.”

Gunton concluded that while investing in large-scale, nation-building projects that diversify exports away from the U.S. has merit, “there is a significant risk of building uneconomic projects that could leave Canadians worse off, especially if the projects are subsidized by taxpayers and expedited by bypassing normal regulatory reviews.”

Janetta McKenzie, director of the Pembina Institute’s Oil & Gas Program, said that after the construction of the Trans Mountain expansion, there was no public discussion of an additional pipeline until U.S.-led disruptions to global trade began. There remains no private sector proposal on the table for the pipeline and no private money invested in developing a proposal, she said.

“A new pipeline would cost roughly $50 billion to build and so far no private sector investors have signaled any interest in taking this on,” McKenzie said. “In addition, a pipeline would only be viable if oil sands producers scaled up production to fill it. This brings significant capital costs as well. Some estimates put this figure around $100 billion. Over the past decade, the Canadian oil sector has been very tightly focused on cost-cutting and efficiency and not on developing new facilities. There’s no indication that industry is interested in departing from this strategy to build large new capital projects.”

McKenzie said Canada needs to develop new industries with brighter outlooks, such as those that relate to clean energy and clean tech supply chains, rather than oil, which is expected to peak within a decade.

“Two out of every three dollars invested in energy globally are now being invested in clean energy rather than fossil fuels, and such investments have multiple benefits,” she said.